Do You Speak Green? A Glossary of Sustainable Design

We recognise that there is a lot to learn when it comes to sustainable design. Despite working with innovative materials and processes for more than a decade, we’re still on our own journey of discovery.

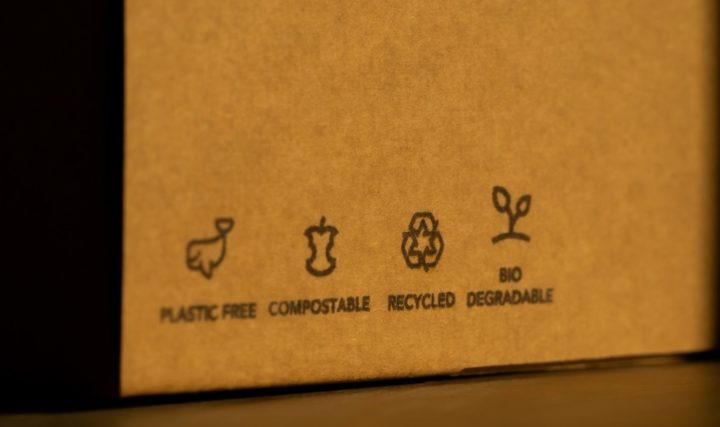

Sustainable design, however, is not simply about recreating the same thing in a more ‘sustainable’ way. Sure, we could switch out our glossy, coated paper for brown kraft – but does that really constitute ‘design’?

Instead, sustainable design is about a mindset shift. It’s about taking a step back to consider the entire lifecycle of a product – where it’s come from, where it is, and where it will be – in order to arrive at a more holistic, considered creative approach. And that, in turn, means placing materials and processes at the centre of the design process.

As a way of enabling this mindset shift, we have compiled a helpful glossary of terms to allow you to start adopting the lexicon of sustainable design.

What follows is an introduction to the key terminology that will allow you to talk confidently – to your colleagues and your audience – about the design choices behind your projects and their impact on our planet.

For the first in our series, our focus is on materials (naturally).

If you have an upcoming project you would like to discuss, or would like more information about any of the terms listed here, contact us via Instagram, LinkedIn or on e-mail via info@nirvanacph.com. We look forward to continuing the conversation.

MONOMATERIAL

A physical surface manufactured from one type of material. Examples include products made solely from paper, glass, cotton, aluminium or one type of plastic. PET bottles commonly used in the food and beverage industries fall into this category.

Mono-materials are typically easier to recycle; as a result, it is likely that there will be local infrastructure to support the recycling process.

MULTIMATERIAL (OR MULTI-LAYER)

A complex surface manufactured from more than one type of material, normally engineered in order to achieve pass specific and specialised performance tests.

A shoe provides an everyday example of a multi-material. Whether for sports, casualwear or eveningwear, shoes almost always comprise of two parts – a sole (including the insole, mid-sole and outsole) and an upper. These parts can be divided into more specific components, including the lining, tongue, eyelet, throat line, toe cap, welt, vamp, heel and quarter.

Each component is required to perform a different function as part of the shoe design. As a result, a range of materials are employed, each with properties specific to the component’s job.

(Until recently, that is. Innovations such as the adidas Futurecraft Loop are challenging the assumption that footwear must be a multi-material, by introducing mono-material propositions to the market.)

LINEAR MATERIAL

Any mono- or multi-material that is designed for disposal after use. In this context, ‘disposal’ refers to landfill, energy recovery or composting.

Compostable materials are linear by nature, since their surface cannot be reused, repurposed or recycled to create a new physical product. Instead, they are diverted to facilities where they decompose to fuel the soil compost.

MIXED LOOP MATERIAL

A recyclable material that degrades significantly each time it passes, or ‘loops’, through the recycling process. Paper and plastic, for example, can only be in the recycling stream for a limited number of ‘loops’.

In general, paper can withstand 4-7 loops before it is deemed unfit for further use. Each time it passes through a loop, the fibres that make up the paper shorten and degrade.

Like paper, plastic cannot be recycled to create a new product of similar quality. Plastic bottles may pass through several loops, but each time their properties will further diminish. As a result, recycled plastic tends to be processed into clothing fibres or furniture – which, in turn, go on to become non-recyclable road filler or insulation.

(Brands including Evian and Coca Cola are investing in research projects to assess the feasibility of bottles made from 100% recycled PET. However, the environmental impact and overall resource consumption attached to large-scale production of 100% recycled PET bottles remains unclear.)

CIRCULAR MATERIAL

A material that can be infinitely recycled without any loss of properties. Glass and aluminium are the two best-known examples of circular materials.

Since the recycling process for glass and aluminium does not require the addition of new (or Virgin: See below) resource, incentives have emerged worldwide to support the development of recycling infrastructure.

As a result, estimates suggest that between 50-80% of all glass bottles are recycled worldwide. In Switzerland, the figure may even be as high as 90%.

And, incredibly, 70% of all the aluminium ever manufactured remains in use today.

However, the recycling process for circular materials has its own impact. For those conscious of carbon footprint, the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) has concluded that a glass bottle becomes a preferable environmental option only after it has been reused at least 20 times.

VIRGIN CONTENT

Raw natural resources harvested for the purpose of material production.

Many papers contain 100% virgin wood pulp (though this is becoming increasingly unfashionable, with a move towards papers comprising a mix of virgin and recycled content). Any piece of clothing, bag or accessory made from organic cotton is also manufactured from 100% virgin content.

RECYCLED CONTENT

Material surfaces manufactured using a proportion of pre- and/or post-consumer waste.

In some parts of the world, recycled content is now required by law. In California, USA, the state legislature mandates that all paper packaging must be manufactured using at least 40% recycled fibres.

PRE-CONSUMER WASTE

Any material discarded during the manufacturing process, before it was ready for consumer use.

PCW may refers to production offcuts as diverse as trimmings from paper production, defective aluminium cans, shavings, sawdust, or even walnut shells. These scraps are often reclaimed and reintroduced into the production of new items.

POST-CONSUMER WASTE

Waste material generated at the end of the lifecycle of a consumer product.

After a consumer product has served its intended use, it will be discarded into a waste stream – landfill, recycling, composting or energy recovery.

Just about anything in your household waste can be referred to as PCW, including food, packaging, magazines or clothing. All have the potential to be turned into a soil compost, or given a second life as a new product, if processed through the appropriate stream.

Posted 05 September, 2024 by Katie Kubrak